“…the best writing is certainly when you are in love.” ~ Hemingway

For many years, all I wrote about was love. In my adolescence, I wrote about my dad, whom I loved and who had moved out after separating from my mom. When a college fling didn’t work out and he told me so on Halloween, dressed like the devil, I flipped that neatly into a story and published it in the literary magazine. For my senior comps—the dissertation required for a Kenyon English major to get her degree—I wrote about the hot Brit who would later become my husband and our travels in Egypt. (I am still mad to this day that I got only a “Pass” and not a “Distinction,” although if I were brave enough to go dig that heap of paper, entitled “Monuments,” out of my attic, I know I’d see all too well why.)

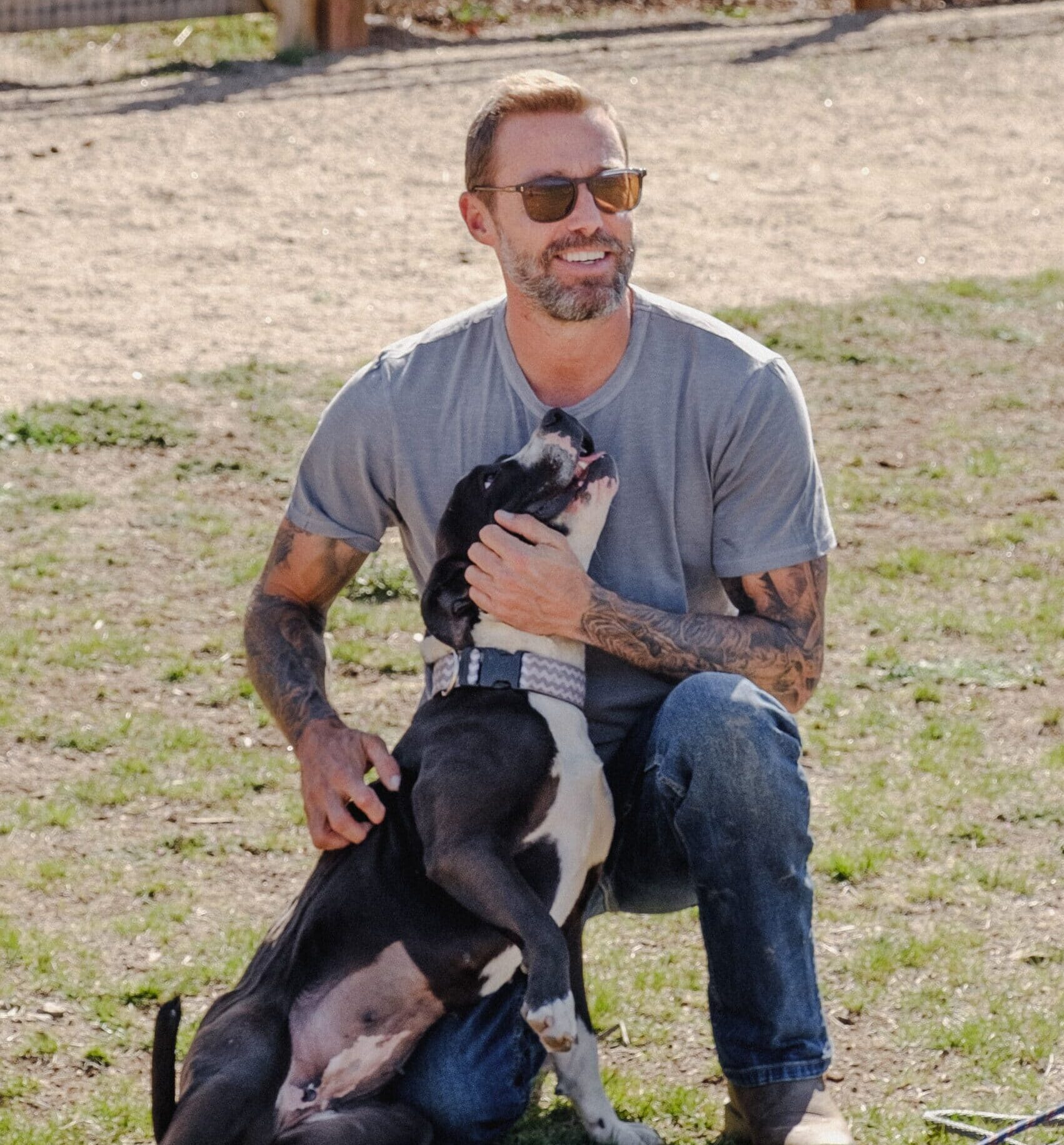

Woodrow and Jenna on the road.

Photo by Jim Reed

When that first marriage fell apart—because I wanted to be a writer, and my husband didn’t get the writing thing—I wrote about that sorrow from his point of view, trying to make peace with the fact that he was going going gone. And after that, I wrote about the men who shifted in and out. The reporter who aspired to be brave as Hemingway’s bullfighters. That guy who the morning after our first date showed up at my door with a Swiffer for my new apartment, which he then moved into for seven years. The pilot who flew into my life, wined and dined me, and disappeared on my 30th birthday, whereupon, in a different uniform, he became an SS officer in my first book.

All that longing, all the sadness, all the sex and hope and rage: I captured all the men and transposed them into stories. It was enough of a pattern that when I went on dates in my 30s, I handed out business cards that said, “WARNING: I’M A WRITER. IF YOU’RE NOT NICE TO ME, I’LL PUT YOU IN A STORY.” I laughed along with the suitors who got it, hahaha, pretending it was a joke. Like most jokes, it had a not-so-pretty truth at the core. I’d fall in love, and at some point it would go dreadfully wrong, and then, burning with sorrow, humiliation and rage, I’d turn it into a story. It was my way of making sense of what had happened. And it would sell.

Woodrow, the “George Clooney of dogs,” charming two lady visitors from Czechoslovakia.

Photo by Jenna Blum

Somewhere between my second and third book, this started to grow old. I wasn’t sure whether it was reliving or writing the story over and over that became tedious, but I decided I was done. No more bad guy stories, delicious as it might be to lampoon a former lover (for years I had a Post-It above my desk: WRITING WELL IS THE BEST REVENGE). I no longer wanted to seek or write about love if it had a constant undercurrent of vengeance. So I turned to different topics: war, trauma, food, big weather, American landscape—all things I loved, but not drawn from the same very personal emotional vein.

And then: Woodrow.

Woodrow was my fifteen-year-old black Lab. I’d gotten him when he was a puppy, with the guy who’d brought me the Swiffer. The Swiffer guy and I didn’t work out, and Woodrow was there. The guy after him likewise, and my fiance: wonderful men who came and went, and Woodrow stayed. When I was in love, he snored. When I had sex, Woodrow got a marrow bone. When I was grieving, he gave me the stink eye: Mommoo, stop crying and get up. The dog has needs, the dog is starving. Whatever happened—a new book, a bigger apartment, my mom getting breast cancer, then passing—Woodrow had to go out three times a day. He had to be fed—all the time, according to him. When I was on the road for book tour, he was in the backseat, catching Smartfood I tossed over my shoulder. He was, as Auden wrote, “…my North, my South, my East, my West/ my working week and my Sunday rest.” My common denominator, my daily joy, the real love of my life.

Jenna walking Woodrow with a Help ‘Em Up Harness.

Photo by Julie Hirsch

When Woodrow was fourteen, he was diagnosed with congestive heart failure. His cardiologist (yes, my dog had a cardiologist) gave him only a few months to live. Woodrow lasted another year. He had digestive issues, to put it politely, and he wasn’t very mobile. His back legs had pretty much stopped working before the heart failure; now I carried him around like an eighty-five-pound log in a sling, using a harness called a “Help ‘Em Up.” I live in a Boston apartment with sixteen steps between my place and the street; outside, we crossed busy Commonwealth Avenue morning and night, no matter what the season or weather. Woodrow did his sniffs on the Commonwealth Mall. Then we stumped to the nearest park bench, where Woodrow whumped down in a dirt patch his body had made, over the years, in the grass. And there we sat, and sat. And sat.

This is the thing: All those years, I’d thought I’d known what love was. And I did: I was smart enough to recognize that my parents loved me, my siblings and friends. I understood what it meant to be loved by a good man and return that love, even if it didn’t work out. I knew what it meant to love my dog. What I didn’t know, what that time on the bench taught me, was the myriad kinds of love, its nuances, the love that came from places you would never expect. First it was neighbors, other dog moms who came to sit, to gossip, show me photos of their kids getting married, lament their parents going into nursing homes. My friend Jacqulene and I played Bachelorette, dissecting her love life. Soon people started to bring us things: carrots for Woodrow, who loved them and ate them like a horse, except now that he had so few teeth, he gummed them to death. Coffee for me. Dog ice cream. And because Woodrow was a canine tractor beam, crossing his long still-elegant legs and smiling down the greenway, total strangers got pulled in, too. A couple celebrated their 57th anniversary with us on the bench. A gorgeous Italian woman sat in the dirt with Woodrow, in her white jeans, and cried. “He is so special, this one,” she said, “he has such a special soul.”

Woodrow on his fifteenth birthday.

Photo by Casey Cokkinias

Facebook friends I’d never met in person found us from the posts I wrote (from Woodrow’s POV, of course), walking up and down the Mall until they spied Woodrow’s bench. My friend John and his daughter Abby from California alighted with us, Abby doing plies with one leg on the bench. My novelist friend Alyson Richman floated to us from Long Island with her husband and son. A mother and daughter I’d never met stopped one evening to say “Oh, thank God, there you are! We thought something had happened to him. We look for you every day.”

It seemed, buoyed up by love like this, that Woodrow might live forever, and indeed he did live so much longer than anyone thought he would. I believe it is the love that did it. The love of travelers, of passing drivers, mailmen and doormen, of the guy who swept the streets for the City of Boston and every day said to Woodrow, “How you doin, brother? Anything I can bring you? Have yourself a blessed day.” That love, various and unexpected, lifted us both up, and when Woodrow did die, one cold and sunny December morning, surrounded on his own bed by ladies he loved, there wasn’t a second of doubt in my mind:

I was going to write about him.

Smashed as I was, shattered—I was insensible for a few days—I knew that the purest homage I could give my old dog was my writing, that this time my writing was the purest form of love. Not writing to capture or to seek revenge on death. But writing to say thank you to Woodrow for the love he gave me, for the love our friends and neighbors and strangers gave us. It was not the best way I knew to make sense of things. It was the best way I knew to give back.

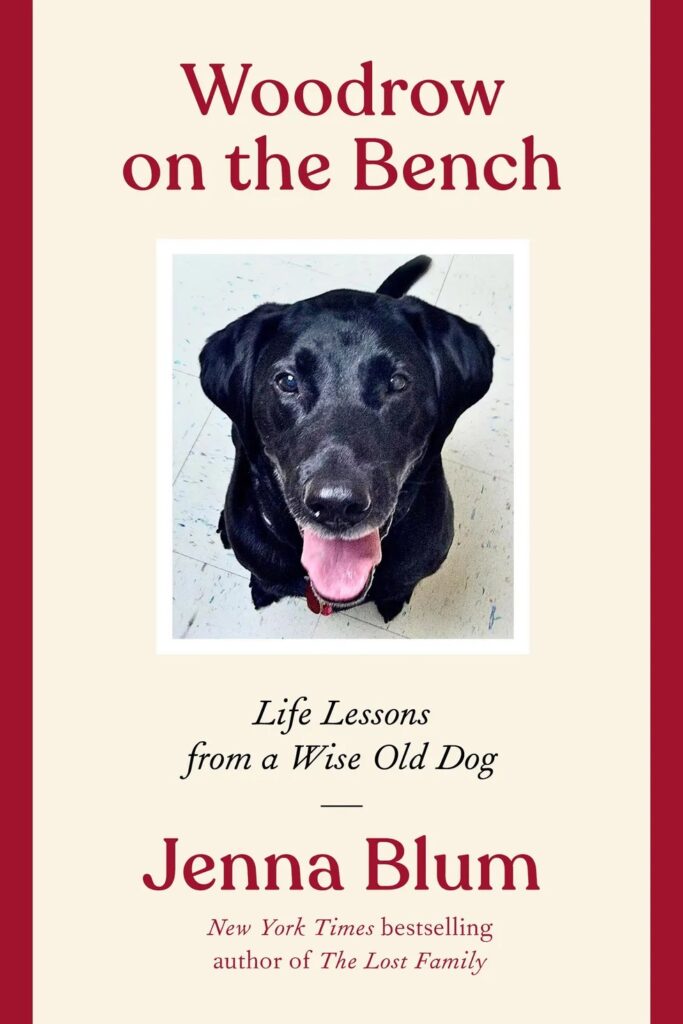

The cover of author Jenna Blum’s new memoir about her dog, Woodrow

You can purchase a copy of the author’s new memoir, Woodrow on the Bench: Life Lessons from a Wise Old Dog, here.

subscription

LOVE, DOG