When my beloved black Lab Woodrow reached the Methuselah age of fifteen, I started thinking about . . . puppies. I felt terrible about it, since Woodrow was still with me. Every day I carried him to his favorite park bench across from our downtown Boston apartment, where we sat while Woodrow held court. I knew, because the one flaw in the otherwise perfect dog design is that they don’t live as long as their humans, that I wouldn’t have Woodrow much longer. I also knew I wouldn’t last long without a dog—I’d never known life without one.

So one morning I started looking at puppies online, casting guilty glances at Woodrow as if I were looking at puppy porn. (Which I was.) Woodrow gazed regally into the distance. Oh, Mommoo. Of course you’ll need another majestic dog presence to grace your human life. Get on with it.

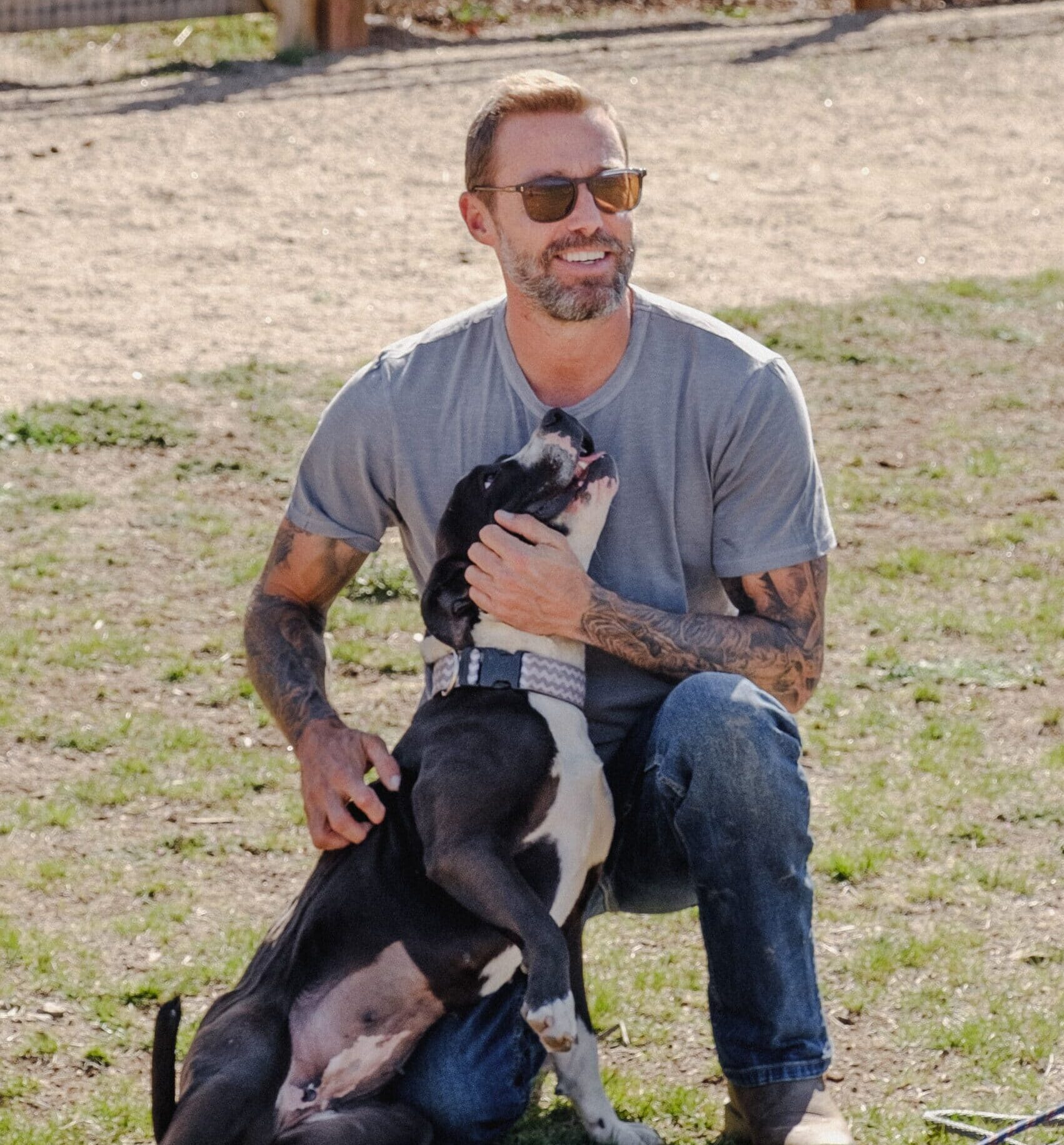

The author’s old dog, Woodrow, the subject of her new memoir, by his bench in Boston.

Photo by Jenna Blum.

Thus blessed, I scrolled through Lab breeders. I wanted to rescue an older Lab, but I wasn’t ready for more senior dog care just yet. (In the back of my mind, I remembered Woodrow’s puppy days were also a lot of work, but I tucked this fact away.) I found a Minnesota farm that bred Labs who looked similar but not identical to Woodrow, called Whispering Pines.

It should have been a no-brainer, reserving a roly-poly puppy. Still I hesitated. When was the right time to get a new dog? How long should you wait after your old dog crossed the river?

There didn’t seem to be consistent advice about this.

“I waited three years between Georgia and Harriet,” my friend Sarah said, gazing lovingly at her current Wheaten terrier. “Mostly because I wanted to travel. It might be nice for you to have a break.”

“We waited a year after Rufus crossed the Rainbow Bridge,” said Megan and Emerson, who now had a pair of Springer spaniels with angelic freckle-faces and WWF personalities.

“I never got another dog,” was a common answer. “I loved my old dog so much. I couldn’t go through that loss again.”

“It’s totally up to you,” said my friend Jacqulene, hand resting on the anvil-heavy head of her black Lab, Rizzo. “I got Rizz a month after my old Lab died, even though everyone said it was too soon, and I never regretted it. There are two things you should know, though. The first is that the new dog doesn’t make your grief go away—he just distracts you from it. And the second? You’ll think your new dog is weird.”

“Weird how?”

“Just weird. Because he’s not the old dog.”

I filed this intel away with Puppies are a shit-ton of work and put down a deposit with Whispering Pines.

Woodrow left this world that December, and I mourned him hard—I miss him now, every day. In midwinter I was still grief-hibernating, tail over my nose, when I got an email from Dan, the Whispering Pines owner: A new litter was due in early spring. Did I want first pick? I paused, sent up a prayer to Woodrow, and said yes. Maybe it was time.

The pups were born in March…2020. The same week Covid-19 shut down the world. I emailed Dan in a panic. What would happen if I couldn’t get to Minnesota to pick up my puppy in May, when he was old enough to go home?

“Let’s see what this Covid-19 thing does,” Dan replied. “It might be over by then.”

This seemed reasonable, so I chose my dog: a stocky little guy my high school BFF Bernadette called Superchunk.

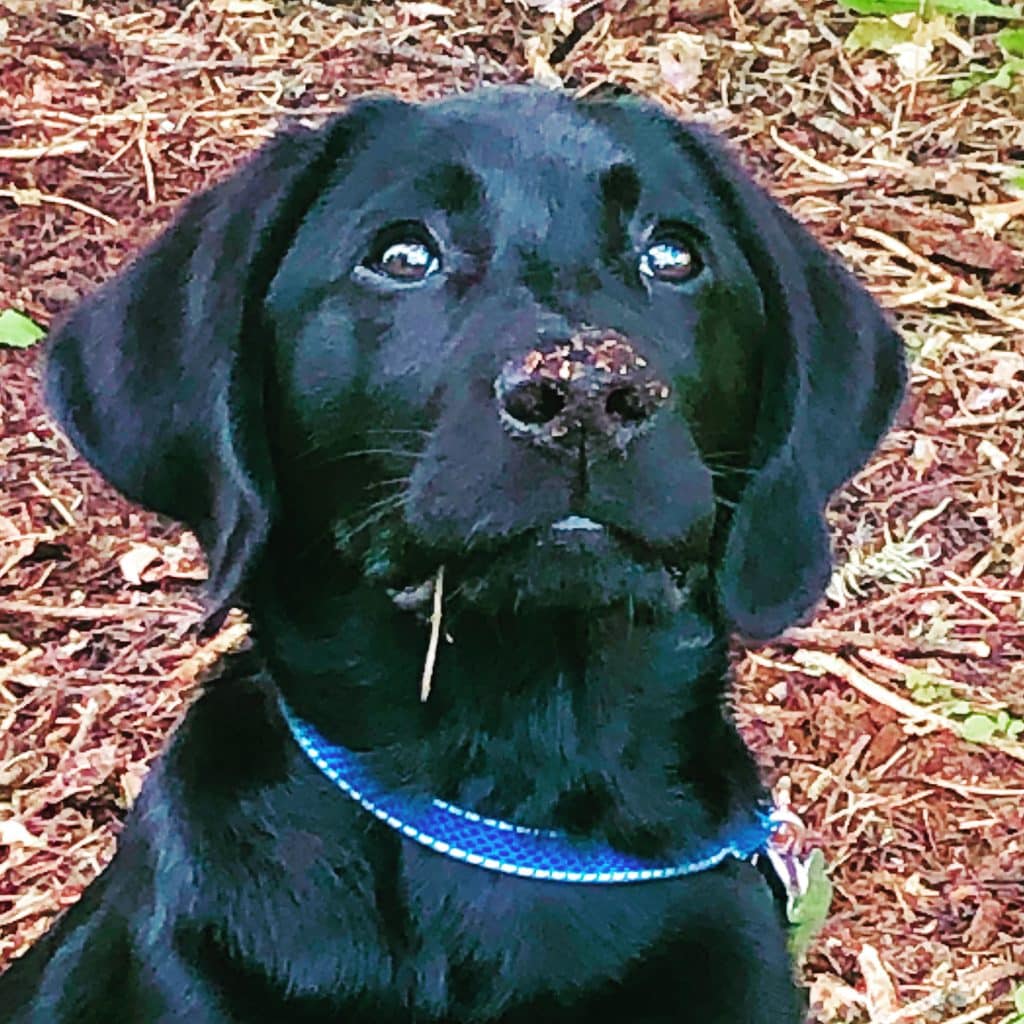

The author’s new puppy, Henry Higgins, aka Superchunk, circa March 2020.

After much obsessive contemplation of names—Walter Cronkite, Walter Mondale, Hubert Humphrey—I settled on Henry Higgins, for the lead in my favorite musical, My Fair Lady. I entertained the quarantined dog parents of Boston with photos and videos of Henry pouncing, barking—an adorable squeak—and wrestling his littermates. My dogsitter Casey started a countdown on a wedding app, ticking off days, hours, and minutes until Henry’s arrival.

April passed and Henry left the birthing barn. In May, he encountered the farm’s horses, goats, and chickens and splashed in his first wading pool. He was growing up without me. “I can fly him to you,” Dan offered. But it wasn’t really safe for Henry to fly solo in cargo—or for me to risk a Logan airport pickup during lockdown.

“Maybe you should consider a pup from a fall litter,” Dan said.

This made sense. And I was crushed. I didn’t know how bonded I’d gotten to Henry until I couldn’t have him. I asked Dan to wait another few weeks—maybe Covid would be over by then? But by June, it still wasn’t, and Henry was the last of his litter on the farm. He’d have to go to other humans if I didn’t jump. So I packed my masks and sanitizer, locked my apartment and headed to Minnesota, where I had a family house in the farm town where my mom and grandma were born, where my friend Jim was living—and where Whispering Pines was.

I drove for two days wearing bandannas and gloves like a bandit, talking to no one, carrying my own bedding and bleach into my midpoint hotel. In Minnesota, I picked up Jim, and we swung north to Whispering Pines. The farm was in a maze of cornfields, accessible by a dirt road, surrounded by the trees that gave it its name. There were the barns where the dogs lived; a neat house, chairs on the grass 6 feet apart. I finally met Dan, and we sat outside with our masks on, talking about the strange times.

Then the kitchen door opened and along with Dan’s wife Mary Jo, a small black creature shot out. He trotted right up to me and Jim, sniffing curiously. HI THERE MISTER AND LADY LIFE IS VERY P-Q-LIAR & INTERESTING. He was tiny and sturdy, with a candlewick tail and black button nose; he squirmed when I lifted him, then settled into my arms. This was Henry, a creature born into a pandemic with no idea of its existence, who greeted the world with only happy expectation.

The author’s first time holding Henry.

Photo by Jim Reed.

“I hate to see this little fella go,” Dan said as he handed over Henry’s paperwork, crate, and food. “He’s a sweet one for sure.”

I cradled Henry in my lap as we left, feeling the way I remembered from bringing Woodrow home: simultaneously as though I were holding a unicorn and…sheer terror. Henry was so dependent. He knew nothing, not how to pee outside, not the difference between food and electrical cords, not how to sleep through the night. What would I DO with him? What canine cherry bomb had I just thrown into my already pandemic-challenged life? But I loved him instantly.

When we got to my family house, Henry squatted in the grass, peed—I praised him extravagantly—and trotted off to eat…Something Bad, as we discovered when he started vomiting.

“He definitely has a mass,” the local vet said, palpating Henry’s pale pink belly. “He might pass it. If he doesn’t, you’ll have to run him up to Rochester for surgery.”

This meant leaving Henry in a clinic alone, since Covid prevented me from going in with him, to have his stomach unzipped. I buried my face in Henry’s fur as the vet gave him an anti-vomiting shot; he yelped and I felt terrible. “I’ve had him less than 12 hours and I already broke him,” I said.

Henry did pass the obstruction, which turned out to be the neighbor’s mulch pile. In the following days and weeks, no matter how closely I watched him, he managed to eat every dead thing within radius. Bats, decaying robins, snakes—one morning he looked brightly up at me with a tail hanging from his jaws. The neighbors grew used to my pre-dawn screams. “He’s a mouthy little guy,” the vet said when I brought Henry in for more X-rays.

“Woodrow never did this,” I said. I heard Jacqulene saying, You’ll think your new dog is weird. On the way home, I looked down to see Henry chewing something so black and leathery it looked like a shoe. WHAT, LADY? Henry seemed to ask as I pried it from him, shrieking. IS MUMMIFIED FROG. IS DELICIOUS!

Mulch is delicious!

Photo by Jenna Blum.

Do you guys have pet insurance? I texted my Crazy Dog Parents’ Group. Has anyone else’s dog eaten deer scat? How about a whole chipmunk? Do your dogs try to climb into the dishwasher? While Henry savaged his toys and lifted his leg on the kitchen rug, I frantically read How-To-Puppy blogs, astonished that even though I’d raised Woodrow, this was so challenging. If you want to give your dog back, one article said, you’re doing it right.

The summer passed. I ran my small business on Zoom with one hand and ran Henry outside every half-hour with the other. He housetrained and learned to walk on leash, graduated to licking dishwasher plates instead of climbing in. I started thinking about taking Henry back to Boston. He was such a country boy; how would he fare in the city? Woodrow had loved it, but Woodrow had been George Clooney in a dog suit. Henry was Owen Wilson in a dog suit, arriving at the frat party and saying, WHO’S GOT THE BONG?, then crushing a beer can against his skull. He was a sweet, blockheaded little creature who loved nothing more than the physical sensations of his dog body.

“I don’t know if it’s the right time,” I said to my friends on Zoom, watching Henry on the porch. He was humping a stuffed chicken four times his size. “On the one hand, there’ll be fewer dead things for him to eat. On the other, there’re discarded masks, gloves, chicken bones, rat poison…. Maybe I should wait until he’s older. Or later this fall? Maybe the pandemic will be over by then….”

It’s always the right time to bring home love.

Photo by Jenna Blum.

Then I realized: There would never be a good time. In Minnesota or Boston, Henry could run away, eat something deadly, get squashed by a car. Puppies and babies, my friend Kirsten had texted: they have so many ingenious ways to kill themselves. Likewise, COVID was raging. The country was on fire. Nothing was safe. And still I’d managed to get out here and get Henry, and every morning when I opened his crate, he jumped onto the bed to lick my face.

We hit the road, Henry in the backseat where Woodrow had had so many good rides before him. I’d been fretting about how Henry would handle leaving the rural environs of his birth state, not to mention a two-day drive, but he sat up straight and looked alertly through the windshield: THIS IS ALL VERY P-Q-LIAR & FUN, LADY. Somewhere in Wisconsin, he gave a squeaky yawn, then curled up and went to sleep. Whatever challenges lay ahead, whatever hot messes Henry found to get into—even during a pandemic: you could make room for joy. It was always the right time to bring a puppy home.

subscription

LOVE, DOG