Last year, my son, in his senior year of high school, the worst year to date of all our lives, made a prediction: Our then twelve-year-old dog, plagued with health problems, would probably pass on when Ethan went off to college. We didn’t take it too seriously, though he’d made similar predictions before. Most notably letting me know I was pregnant before I knew myself, and then rightly predicting the baby would be a girl. There had always been something uncanny about my son. It was something I loved about him.

He’d always been close to Henry. Ethan had been a dog person since he was a tyke in a stroller. “Goggy!” he’d shout. He’d pet all the pettable dogs and instinctively gave space to the ones who were less so. He’d learned to walk in Miami launching himself between my friend Dafne’s two rambunctious Golden Retrievers, gripping tightly their fur and toddling along. By the time he was five, we were stable enough to finally get a dog of our own, and that was Henry, our Papillon. I’d fallen in love with a Papillon at our vet’s office when I was in my early twenties and had always thought that if I were going to get a dog, that would be the breed.

I’d lived my entire life with cats. My family was strictly a cat family. My parents didn’t even seem particularly to like dogs. Dogs were smelly and they barked inappropriately, and you couldn’t really leave them. We had Siamese cats, always two, and I didn’t even really know how to own a dog. A Papillon was cat-sized and, like cats, highly intelligent.

Henry arrived into a bit of a mess. We’d moved into our first house. Our own Siamese cat had just had a litter of kittens and was protective and hateful. Ethan’s sister was nine months old. Things were chaotic. But I wanted Henry to be a good dog, a well-behaved dog. I worked hard on Henry, as hard as I could, and even hired a trainer. But the trainer gave up almost immediately. “He’s too intelligent,” the trainer said. “I’ve never met a dog quite like him. I don’t think he’s trainable.”

But it was okay. We learned to live with the behaviors we couldn’t change. Henry never could walk on a leash properly. He pulled and lunged, and he was never one hundred percent housebroken (most Paps aren’t). He would leave little messages along the edge of my rugs, messages I’d frantically clean with special detergents and vinegar. But he had an enormous heart and loved all of our friends as if they were his family. Still, he loved Ethan the most. He’d been Ethan’s dog right from the beginning. He spent the first two nights in a crate beside me in bed, and then I handed him off to Ethan where he spent the next twelve years.

When Henry was five, we brought Lucy, a black-and-white Papillon. Where Henry was gregarious and cared more for affection than food, Lucy was the opposite. She was shy and retiring and would devour all the food before Henry. We didn’t have to train Lucy; she did whatever Henry did. If we tried to pet Lucy or otherwise show affection for Lucy, Henry would block her with his body, sometimes emitting a little warning growl. We all accepted this. Henry was the alpha—it often felt like he was the alpha of the entire house—and Lucy was the beta. We added another cat. The kids grew up. Everyone got older. Life was busy.

***

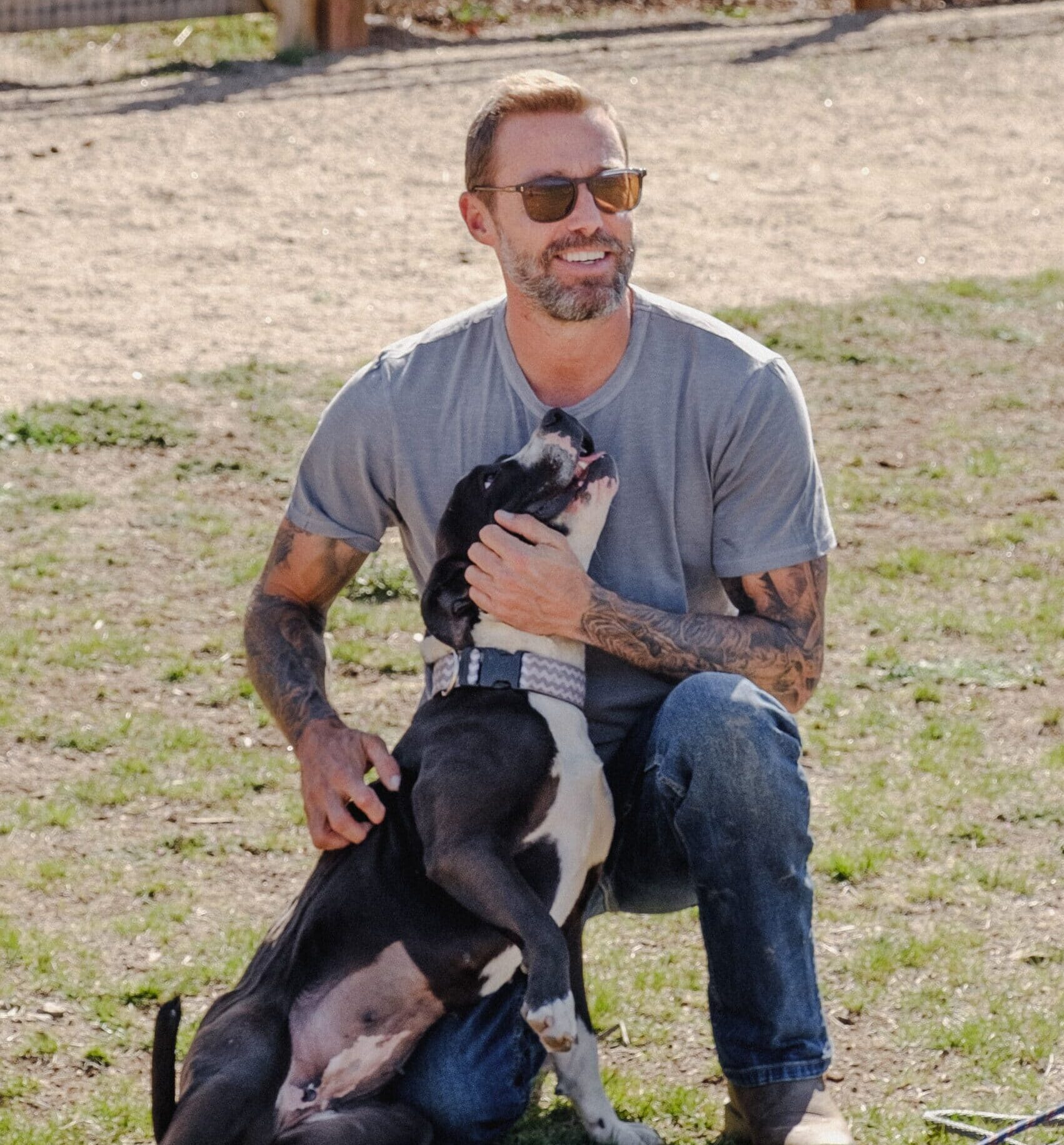

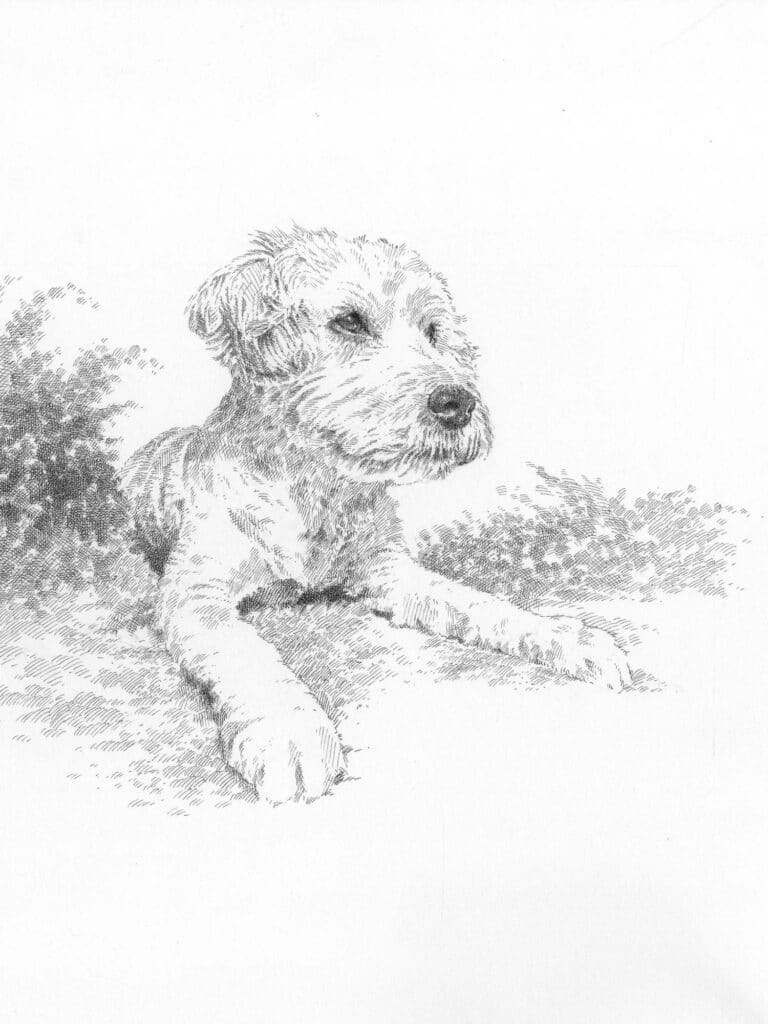

Henry, the family’s first Papillon.

Photo by Bethany Ball

I’d never had a dog before, but I’d been adopted by several. As a child I’d head down to the woods outside Nashville where my grandparents lived. I’d ignore my grandmother’s warnings to watch for the rattlesnakes and I’d head right out into the trees. I’d climb them, or maybe run through the pastures where the old horses lived, trying to screw up the courage to jump on the back of one. Invariably a dog would bound out into the pasture to join me for the week or so I was there. Once it was an old, kind German Shepherd and other times it was a big, red dog, a ginger like me. And then we’d have to head back to Detroit, and I’d have to say goodbye. While I loved those dogs, it was a temporary kind of love. I was a cat person, in the end.

At home, during the day, I took care of the whole menagerie. After the kids went to school, I’d roam the rooms of my house trying to find a place to write, and the dogs and one or the other cat would follow me. We had a big back yard and a thirty-acre meadow across the street that ended at the base of a mountain, and if I was stuck in my work, I’d walk with them out there and let them race across the meadow, chasing deer. I fed them each morning, I took them to the vet, I cleaned up their accidents. It was a perfunctory sort of relationship that I had with dogs. Cats I understood; the dogs I sort of tolerated.

In fact, it wasn’t until the pandemic that I fell madly in love with them. Henry especially. When I was down, when I was lonely, there was Henry as boundlessly optimistic as ever. Lucy remained a shadow of Henry, even as he grew older and thinner and more feeble. But that was okay, too. They were a pair. Then my son went through a bad break up, and Henry stuck by his side, often lying across his chest to comfort him. But during those days, his simple presence was comforting to all of us.

It occurred to me that I’d had this magnificent, complex, deep creature in my house for twelve years and had never learned to appreciate him. I’d never learned to appreciate dogs at all. I realized I loved him wildly, intensely. I understood something new about love. I was a dog lover. Finally, I got it.

The author’s daughter, Cecily, taking Henry for a walk.

Photo by Bethany Ball

A few months into the pandemic, Henry began to cough. He coughed for two days straight until I could get him to the vet. It was an enlarged heart, I was told. We were given medicine and it was over a hundred dollars a month and we had to give it twice a day. Henry hated the medicine, and being the stubborn, ingenious creature he was, he could eat anything we wrapped the medicine in and then spit out the pill. I tried all manner of methods and foods. Salami, cheese, ham, salmon, yogurt even. After a while we had to force him to take it and then he’d snap at us. He never bit but he frightened me. Cats with their claws and teeth and sudden movements I understood, but I guess I’d read too many Daily Mail articles about dogs eating their owners’ faces off and I never did stop being afraid. Finally, I crushed the medicine and fed it to him with a dropper, but even then he’d snap. Then one day, he stopped coughing. We sighed in relief. He seemed better.

My son left for college in August. It was a long, difficult journey getting him there. Covid had been difficult for him, and I wasn’t sure he’d stay. He had never spent more than a few nights away from his home, from us, from Henry in his life. He was there to play Division 1 tennis but had a heart murmur that needed to be cleared and couldn’t practice with the team, prolonging his adjustment. He was spending the weekend at home when Henry had trouble breathing. He called us, crying. We raced home from where we were, running errands, but he was gone before we could get there. He’d died upstairs in the living room. Ethan had picked him up and brought him to his bedroom, where Henry had spent so many nights, and placed him in his bed. He was inconsolable. “I lost my best friend,” he said.

We are a meditating family, and so my husband laid him out on a velvet footstool Henry had loved, and we left him there surrounded by flowers from the garden for twenty-four hours. Later, my son and husband went out into the backyard to a small secret garden behind some bushes where I’d laid the ashes of my mother, and they dug a small hole. We all cried a lot, but especially Ethan. “He taught me about friendship and loyalty,” he said. We’d brought Lucy with us. Our cat Hugo came, too and he also had some words to say.

My son went back to college and texted us: “I believe Henry’s passing is a coming of age.”

The author and Henry.

Photo by Bethany Ball

Ethan and Henry, with Lucy in the background.

Photo by Bethany Ball

For the next few days, we were grief-stricken, but we also had to contend with Lucy, who we soon realized could not do any sort of simple task without Henry. She didn’t know when to eat and she didn’t know when to go to the bathroom. Though we’d long had the freedom to simply open the door and let the dogs out back, Lucy wouldn’t budge. It was then we understood that Lucy was a dog’s dog. While Henry had been our dog, Lucy had been Henry’s.

So, two or three times a day, we put a leash on her and led her out into the backyard. I’ve never loved walking in our village, but now, with Lucy for company, I did. Until then, I’d always preferred to walk around New York City, where we have a small apartment. I brought her with me there and discovered that, like me, she loved the city most of all. We understood only now that she loved riding in the car, and so any time we went anywhere, we tucked her in beside us. And she liked to be pet, all around her ears, her neck, her chest, her back—anywhere really. We’d never pet her much, but we found her fur to be unbelievably soft and silky.

Over the days, Lucy came to life. Her ears picked up. We still had to walk her to get her to go, but I started to enjoy our time outdoors together. Even as I write this now, I’m sitting outside at an Indian restaurant on Avenue B in New York City. She is calm and patient, doesn’t pull on the leash. Henry showed me how to love dogs, and Lucy became the dog I could lavish that love on.

Today, I’ve spent my time walking all over the city like the flaneur I’d always wished to be. I walked from McNally Jackson back to the Lower East Side and up to Book Club on 3rd Street, where dogs are not just welcome but encouraged. I’m not an aimless walker. I type destinations into the app on my phone and walk with my head down hoping not to make a wrong turn. With a dog everything is different. Your purpose isn’t to get from A to B but to meander, smell and see the sights, admire the other dogs, perhaps try and pull your owner into the cheese shop on East 12th Street.

I’m dragging her around by the leash of course but at the same time she’s dragging me. Because I never walked both dogs much I never found out what her preferences were. Even had I walked both dogs, I wouldn’t have known. She had none. She did whatever Henry wanted. She likes to walk on the side of the street beside the buildings even if we are walking against the traffic of the sidewalk. The better to sniff and pee on the brick and stone and concrete. She lifts her leg like a male dog. Every other open door she tries to scurry in. There’s no rhyme or reason. Now it’s a pizza place, which makes sense, but now it’s an eyeglass shop, a perfume place. At the Book Club she’s given a cup of water and some biscuits. She quietly sits under my chair and observes the atmosphere. In fact, she IS the atmosphere she’s helping to create. Dogs come and go, and she’s peaceful. And then a dog comes in, a kind of long-haired Pug type, and all the dogs in the place go nuts. Including Lucy. That Pug is another agent of chaos, I think. Like Henry. Stubborn and alpha.

I have come to understand something about love and dogs. You don’t love a dog because they are perfect, but because their love is.

You can purchase a copy of Bethany Ball’s new novel, The Pessimists, here.

subscription

LOVE, DOG