On July 5, 2024, we released a podcast episode featuring a conversation with Zach Skow. You can listen here.

In 2009, if you were in downtown Bakersfield, or Tehachapi, CA, you may have come across a yellow man with a big belly putting up posters of dogs for adoption. With him was a 95-pound Rottweiler-Pit Bull mix. The dog’s name was Marley. But who was the man?

No one could possibly know it at the time, but in the years to come, this mysterious figure, Zach Skow, would become one of the most recognizable faces in the world of animal rescue. He would go on to found Marley’s Mutts, a rescue organization that would be profiled in Oprah’s O magazine and would be directly responsible for saving the lives of 7,000 to 8,000 dogs. In 2011, Skow would receive the American Red Cross Real Hero award. In 2021, he would make an appearance on Ellen.

But back in 2008, Skow wasn’t even sure he would survive another six months.

~

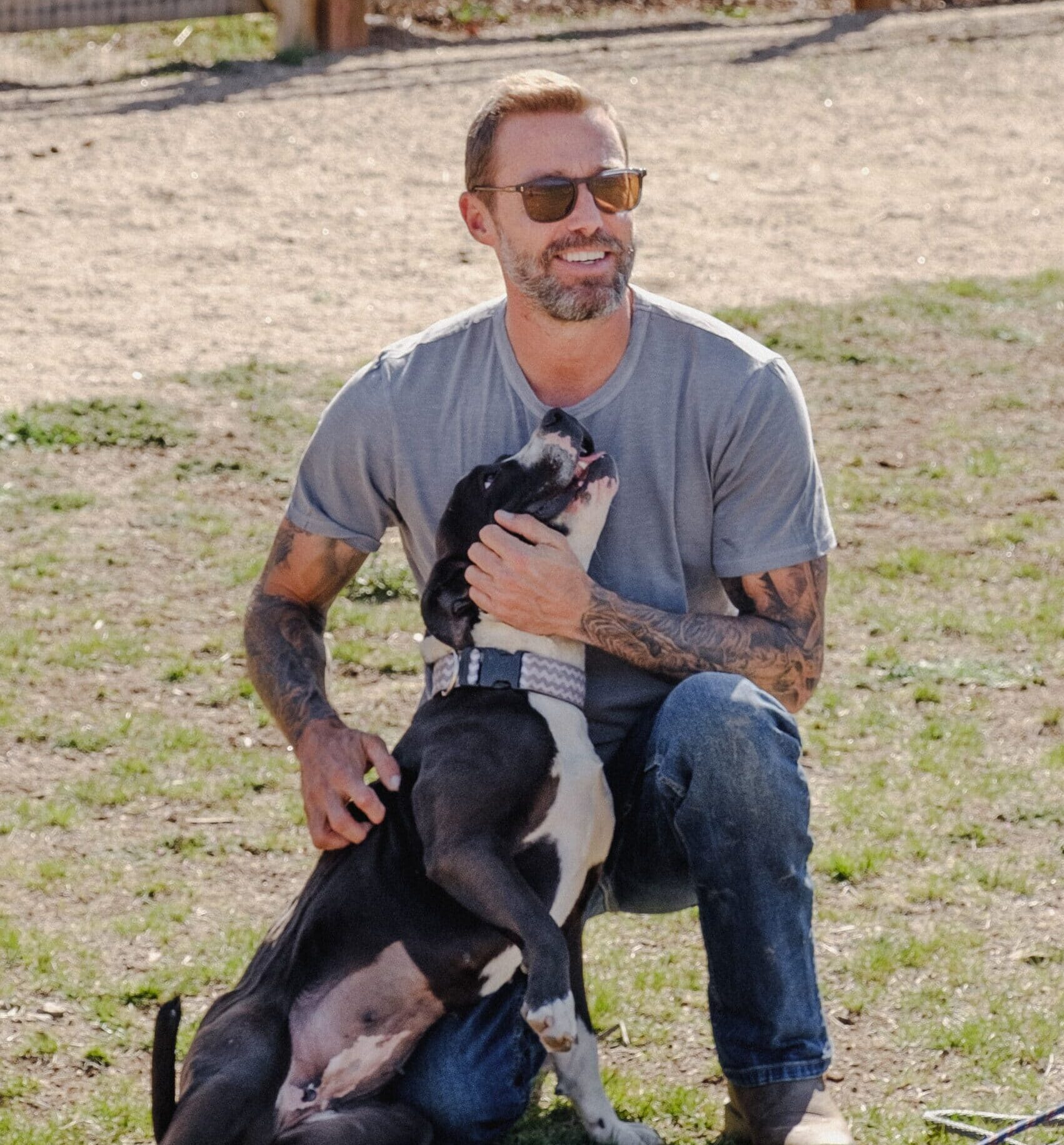

Photo by Ben Potter

In March of 2008, Skow was diagnosed with end-stage liver disease. He had been drinking since he was a young man. The drinking persisted and his health worsened. At only twenty-eight, his skin had turned yellow, and he was coughing up blood. The prognosis wasn’t good. At the hospital, he was told he would need a liver transplant. Without it, they estimated that he had ninety days to live. The issue was that he couldn’t get one for six months.

Skow wasn’t eligible for two reasons. The first was that he wasn’t healthy enough. The second was that alcoholics and addicts need six months of sobriety to qualify for a transplant. This began a six-week stay at Bakersfield Memorial Hospital. As the weeks passed, his condition worsened. Every day, his dad would visit him at the hospital and tell him that he needed to come home because he “couldn’t get Tug to come in the house.” Tug, a loveable and neurotic Labrador mix, was just sitting outside, looking down the driveway, waiting for his dad to come home.

Unfortunately, there wasn’t much more the doctors could do. They suggested Skow be transferred to hospice care. Skow’s father, an aeronautical engineer, wouldn’t stand for that. He approached his son’s condition as a problem that had a solution. He got his son an appointment at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center’s transplant program. At Cedars, he was informed that he would be able to get the transplant, but he would still have to wait six months. They sent him home and told him to stay near an emergency room and to do his best to survive.

Tug was there to greet him. “Needless to say, Tug was elated to see me,” says Skow. “It was like his life could finally go on. I think he’d been holding his breath for six weeks.”

~

Zach at Marley’s Mutts

Photos: Left and right, by Ben Potter

About a month out of the hospital, Skow relapsed. His father had gone on a work trip to Brazil for forty-eight hours, and Skow found the backup keys to his father’s truck. He bought a double bottle of wine and woke up two days later. “When I told him that I drank again,” says Skow, “it devastated him. I’ve never seen him that messed up . . . he was weeping. And he just kept telling me that I’d killed myself.”

A key component of sobriety, Skow shares, is finding a connection to a power greater than one’s self. During the six-month waiting period, Skow was required to attend AA meetings daily. At these meetings people would speak of their connection to God, or a power greater than themselves. One day, “somebody came into the recovery meeting whose dog was his God,” Skow explains. “He didn’t actually believe that his dog was God. He was just trying to funnel his thoughts and his focus to something other than his own ego and his own narrative.”

This helped Skow with his own journey to sobriety, and he soon found a connection to a higher power through his grandfather, a man his father spoke of little and who had also struggled with sobriety—dying of liver failure at the age of forty-one in 1963.

“So, I started communicating with this grandfather of mine that I’d never met, and I would just try to be quiet and sit outside and do my best to meditate. And remarkable things started to happen . . . I started to really realize what constructing a God of your understanding means—that there’s God, there’s holiness, and there’s godliness in just about everything around us . . . in our dogs and the great blue sky and the stars at night. There’s just so many things that overwhelm us all that can allow us to connect to the divine. And I’d been locking myself out of that for a long time.”

One night in 2008, Skow found himself staring in the mirror. He was naked, yellow, and bruised. His arms were sweaty, muscles atrophied. His stomach was swollen. His belly button was herniated. He was covered in varicose veins. “I was utterly pitiful and hopeless. And I just started to sob,” shares Skow. “I thought this is my rock bottom. There’s no reason for me to be here. I can’t do this anymore. I didn’t have it within me.” As he began to sob, he noticed his dogs Marley, Tug, and Buddy watching him, full of a love for him that he seemed unable to give himself. They didn’t care that he was yellow and bruised, or that he had a big scar from a catheter that was in his back to drain his stomach of the blood and bile that had settled there. All they saw was the guy who rescued them. They saw their father. It was right then that Skow decided that if he couldn’t keep going for himself, he would keep going for his dogs. “That day,” he says, “became the first day of the rest of my life.”

~

Photo by Ben Potter

The next day, Skow began to walk. He still had ammonia built up in his brain. He couldn’t balance himself easily, and it was a struggle to walk. But he set out with his three dogs anyway.

Skow had rescued Marley back in 2002 from the Mojave Animal Shelter when Marley was eight weeks old. At first, he did his best to keep Marley hidden from his dad and would carry the little guy around in a backpack with his furry head poking out—but eventually Marley got too big for that game. Elegant and graceful, Marley was a dog who didn’t doubt himself, a dog who broke up fights. “He didn’t like chaos in the pack. And it really helped me because I needed a dog that knew how to keep things on an even keel, and Marley was a pro at that.” Tug, on the other hand, was quite the opposite. He had taken on all of Skow’s fears and was marred by insecurity. Then there was Buddy, a delightful Cocker Spaniel-Dachshund mix that Skow got all the way back in 2004 (he’s eighteen and a half now).

Yet that first day, even with his beloved dogs spurring him on, Skow couldn’t make it up the hill. But the second morning, with dogs in tow, he did. It was six in the morning. It was cold but beautiful. The sun rose in front of him as he worked his way up the hill amongst the mountains of Tehachapi. A great shadow appeared before him. At first, he thought it might be a bear. He’d come across bears on hikes like this before. If it was a bear, he was screwed. He was in no shape to run away nor to pursue his dogs if they made chase.

It wasn’t a bear. It was an old man bundled in a huge parka, shuffling his way up the hill. Skow had never seen this man before, and it was strange to see someone else out on the trails so early. Marley, who was normally one to let Skow know if there was a threat, was calm. Seemingly indifferent to Skow’s yellowed appearance, the man asked about his dogs, and they continued on together.

At this point in his life, Skow shares, all he knew how to do was feel sorry for himself: “That’s how I got what I needed.” Wendell, the man Skow had just met, didn’t do any of that. “He talked about how this was his first time on that walk since losing his wife. And he didn’t feel sorry for himself. He just lost the thing that mattered to him most in this world . . . and he’s strong. I was like, I need to be like this guy.”

Over the next eight months, the two men took more of these walks. Wendell, who went by Wen (pronounced “when”), lived about a mile away, and he and Skow would get up each morning and meet at the top of the hill and take their walks, joined by Skow’s dogs. During this time, Skow added more dogs to his pack. There was a Pit Bull named Vinny whose ears had been cut off. Another was named Chance. Skow still struggled, but with the help of Wen, the walks, and his dogs, he was starting to feel better.

“At that time my depression and my overall worthlessness was overwhelming,” says Skow. “But when I started to add dogs into my pack—sick dogs in particular, dogs that needed help—there wasn’t a lot of time to think about my own shit.” The idea of being of service had entered Skow’s life, and it revolutionized every part of it. He poured himself into volunteering—for the Humane Society and the Canine Canyon Ranch—and he dedicated himself even more completely to his own dogs, too. “I found revival within myself because I found purpose. I had these dogs that 1,000% depended on me for their future . . . I don’t know that I’d ever had a purpose in my life, other than to hyper-focus on my own shortcomings. But then I started working with dogs, and I knew instantly that I was good at it.”

~

Photo by Ben Potter

After six months of sobriety, Skow went back to the hospital for his review. There was good news: he was told that he no longer needed a transplant, that whatever he had been doing was working. The next step was figuring out what to do with his life. He hadn’t expected to make it this far.

Starting Marley’s Mutts wasn’t Skow’s plan. He was just trying to survive. But as he was sorting out what to do next, a friend who worked at the Pet Lodge behind the veterinary hospital suggested that he should try to open a dog rescue. She even came up with the name (Marley frequently accompanied Skow on his visits). She saw that he had been accumulating rescues over the last six months and that he had a knack for it. However, Skow thought it unlikely that the IRS would grant him nonprofit status right off the bat. A lawyer confirmed his suspicion. “To them, I was just a drunk with a dream to save animals,” says Skow. The lawyers suggested that he take some time to build out a body of work before submitting an application.

Skow got to work. He set up Marley’s Mutts as a DBA. He started with $0 in the bank, but Skow was resourceful. He bought t-shirts at Target and K-Mart, his friend Chris designed a logo, and he made iron on transfers and sold the shirts at adoption events and Stag meetings. Eventually, he raised $3,500, more money than he ever had, and with that he welcomed his first litter of puppies. But tragedy struck. They had parvo, a highly contagious viral canine disease. Five out of the eight dogs died. Three were lost in one night. It destroyed him and ate up all of his savings. He felt that he had failed, that his career in dog rescue was over. The next day he attended a men’s group meeting and shared what had happened. The men in his group refused to let him quit. He left the meeting with $800 to help Marley’s Mutts get back on its feet.

He kept going, and by March of 2010, when he submitted his application, he had facilitated around 150 successful adoptions. He’d spoken at schools and churches, and had been of service non-stop. Then, on his second sober birthday, October 12, 2010, he was granted 501(c)(3) status, and Marley’s Mutts was officially born as a non-profit.

~

Photo by Ben Potter

Today, Marley’s Mutts occupies a twenty-acre ranch two hours north of Los Angeles. It’s a majestic, open, and welcoming space. The brilliant blue sky stretches above, meeting the mountains to the East. It feels like the cozy opening of your favorite western, except at Marley’s, there are no bad guys. With a staff and team of over twenty, Skow is still out there doing the work. Marley’s Mutts is on a mission to rehabilitate both human and canine souls and, as they put it, to create “second chances using the power of the human/animal bond.” They offer training, rehoming, and networking. The ranch houses around seventy-five animals. Another fifty to seventy-five are in foster care, and twenty to thirty live in prisons as a part of their Pawsitive Change program. They’ve rescued dogs locally, frequently partnering with Kern County Animal Services and the city of Bakersfield, and they’ve also rescued dogs from South Korea, China, Africa, Brazil, Romania, Mexico, Thailand, Vietnam, and Turkey. Their Motor City Mutt Movers Program brings dogs from overpopulated shelters to underpopulated ones, where dogs are in greater demand for adoption. But the program Skow is most proud of is Pawsitive Change.

Pawsitive Change is a comprehensive inmate canine training program that combines vocational training with canine rehabilitation. They take dogs from high kill shelters to prisons where they live with incarcerated individuals. Through teaching the inmates canine-handling skills, the inmates’ own emotional awareness is developed, and they leave the program with a new skill. Pawsitive Change has a 100% success rate with no recidivism among graduates. With its solid record of achievement, Skow is looking to expand and grow the program, and hopes to bring Pawsitive Change to correctional facilities across the U.S. and the world.

Zach Skow bringing his dogs to the A-4 Yard at North Kern State Prison

Photo by Sarah Deremer

A prisoner bonding with a Pawsitive Change pup.

Photo by Sarah Deremer

A Pawsitive Change pup at the A-4 Yard at North Kern State Prison.

Photo by Sarah Deremer

Like they did for Skow, the dogs help the inmates learn to be present. “If you’re feeling angry, upset, pissed off, tired, lonely, you’re going to negatively affect that dog with that energy.” The people he works with in prisons haven’t always had the opportunity to be vulnerable in the way that the program allows them to be. “I’ve fallen in love with more people in that program than you could ever possibly imagine,” Skow shares. “There are so many people worthy of love, that have been completely starved of hope, love, and positivity. I think what gets lost is if you can live in that dark of an environment and come out with your humanity still intact, you have something valuable to share with the world.”

Roughly half the men who’ve graduated and been released now work as part of the animal welfare industry. “The biggest need that we have within the pet space are trainers, and our programs are producing them.” But working in animal welfare isn’t easy, and it takes an emotional toll. “You’re constantly confronted with very heavy realities,” shares Skow. “And no matter how hard you work, it never seems to be enough.”

One person can’t save every animal, or person. You need a community to do that, and this is a community that is there for each other. “We even have an emotional support text thread that we get on,” Skow explains. He also makes it clear that shelter workers are the unsung heroes of their work. “They’re the ones advocating with rescues to get dogs out. They’re the ones helping us with getting dogs fixed and vaccinated and networking.”

But it’s an uphill battle. Even with all the heavy lifting being done by rescues and shelters, they can’t keep up with the constant flow of surrendered and stray dogs. The result: far too many dogs are being euthanized—especially larger breeds like Pit Bulls and Huskies. Skow makes it clear that shelters are not killing dogs because they want to. “Animal shelters euthanize animals because of space, not for any other reason. They euthanize them because dogs keep coming through the door.” He believes that one solution is for more people to be brought into adoption. “I think that the process of adoption has been far too elitist and exclusionary. So, what’s better: that the dog dies, or that they end up in a home that maybe isn’t 100% perfect?”

Photo by Ben Potter

In a recent Instagram post on @zachskow, Skow delves deeper into this tragic topic, sharing that one of the ways they’ve been battling this soaring trend of dog euthanasia is through their Pawsitive Change program, which sends as many at-risk dogs as they can into prisons. This will not only save their lives, but also it sets the dogs on a path towards therapy certification, adoption, and service. He writes, “Inside, they’ll be guided into a structure of rules and boundaries, while being loved into deep, meaningful relationships with humans they learn to trust and seek direction from. If we had the funding and support, we could have pity prison programs all over the state and maybe then we could stop the needless killing of our society’s abandoned pets.” Just this week, they introduced six Pit Bulls and two Huskies to their temporary home and rehab center inside the A-4 Yard at North Kern State Prison. And next month, Marley’s Mutts is launching a #PowerToThePitties campaign to raise $100,000 to bring attention and resources to this most misunderstood of breeds—the shelter Pit Bull—the very same breed that saved Skow’s life.

As the advocacy and work of Marley’s Mutts and the animal rescue community at large continues, and as more people grow to understand the plight of animals and develop empathy for them, Skow hopes humans will become more empathic towards one another, as well. After all, it’s not only dogs that deserve a second chance, but people, too. If others hadn’t believed in him—if his dogs hadn’t believed in him—Skow knows he himself might not have made it. “People want to slow-clap and be like, ‘You’re so strong. You’re so strong.’ I wasn’t really, in fact,” Skow makes clear. “I was the opposite of strong so many times, you know, and it was powers outside my influence that kind of stepped up and made things happen.” It was other people who believed in him and thought he could do it—his father, Wendell, his friend at the shelter who pushed him to start Marley’s Mutts, the men at the group who helped him with the funds to keep going. They helped him when he was unable to help himself. And as a result, he healed. He grew.

And now for others, Skow can do the same. He can believe in them when no one else does. Whether it’s building futures with Pawsitive Change, or helping dogs find new homes so they can live another day, he can offer what he himself was given: a second chance.

subscription

LOVE, DOG